🌱Seed 🙂Agree 🛠️BringingLifeintotheWorld

The Big Idea

The idea of gardening is foundational to Digital Gardening. It is an alterative way of “being” in digital space that is not time bound. It is opposed to the stream like interfaces of email, social media (Facebook, TickTok etc.), text, etc. that all bombard us with content that will pass us by if we don’t keep up with the stream.

This is intriguing to me because I find it difficult to share ideas in a sustainable way. My ideas do change over time as I learn more or new things. Or as life experience challenges things. Formal writing kind of “freezes” ideas in a very polished and presentable way. Which is fine for more broad distribution of things like I don’t really want some passing thought I had on the toilet branded as my hard and fast worldview on a subject.

But on the other side of things stream based communication is exhausting to always be trying to keep up or just chuck stuff out there for it to be lost to the flow of new things in the blink of an eye.

A garden offers a nice in between. Ideas don’t have to be perfectly polished and change and grow over time. They also have a stable place to live rather than being lost in a feed. This is because a garden functions in iterative and topological fashion. A note is never done and notes are linked to other notes that are related. In this way paths are formed linking like ideas together and helping inform one another and “grow” then as an overall landscape of thought.

This was a useful summary for me to get a handle on what this idea actually offers:

Quote

The Six Patterns of Gardening

After reading all the existing takes on the term, observing a wide variety of gardens, and collecting some of the best examples, I’ve identified a few key qualities they all share.

There are a few guiding principles, design patterns and structures people are rallying around. This amounts to a kind of Digital Gardening Pattern Language.

1. Topography over Timelines

Gardens are organized around contextual relationships and associative links; the concepts and themes within each note determine how it’s connected to others.

This runs counter to the time-based structure of traditional blogs: posts presented in reverse chronological order based on publication date.

Gardens don’t consider publication dates the most important detail of a piece of writing. Dates might be included on posts, but they aren’t the structural basis of how you navigate around the garden. Posts are connected to other by posts through related themes, topics, and shared context.

Because garden notes are densely linked, a garden explorer can enter at any location and follow any trail they link through the content, rather than being dumped into a “most recent” feed.

Dense links are essential, but gardeners often layer on other ways of exploring their knowledge base. They might have thematic piles, nested folders, tags and filtering functionality, advanced search bars, visual node graphs, or central indexes listing notable and popular content. Many entry points but no prescribed pathways.

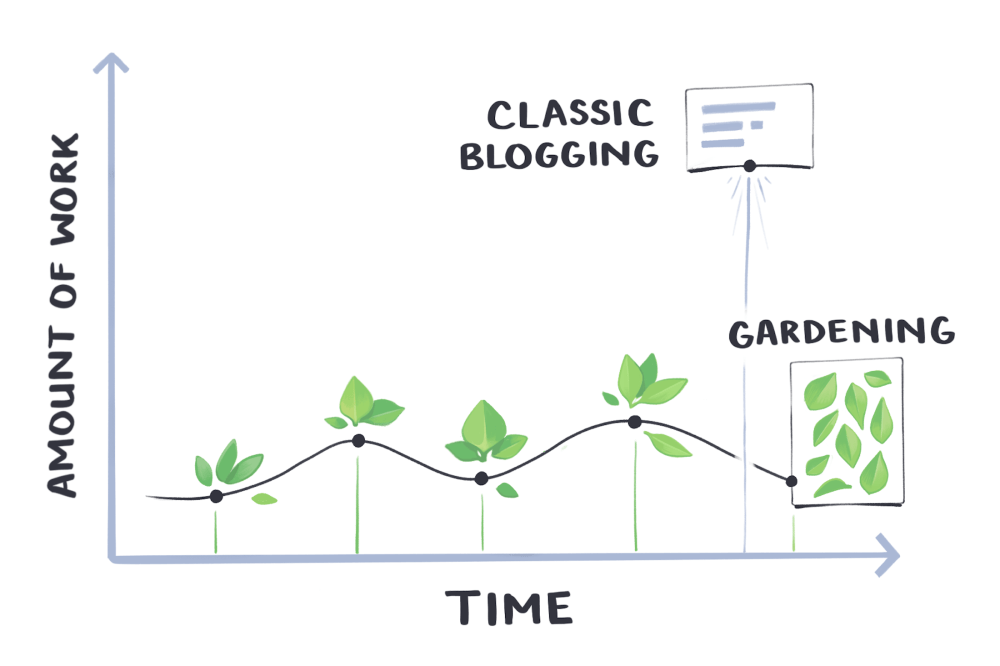

2. Continuous Growth

Gardens are never finished, they’re constantly growing, evolving, and changing. Just like a real soil, carrot, and cabbage garden.

The isn’t how we usually think about writing on the web. Over the last decade, we’ve moved away from casual live journal entries and formalized our writing into articles and essays. These are carefully crafted, edited, revised, and published with a timestamp. When it’s done, it’s done. We act like tiny magazines, sending our writing off to the printer.

This is odd considering editability is one of the main selling points of the web. Gardens lean into this – there is no “final version” on a garden. What you publish is always open to revision and expansion.

Gardens are designed to evolve alongside your thoughts. When you first have an idea, it’s fuzzy and unrefined. You might notice a pattern in your corner of the world, but need to collect evidence, consider counter-arguments, spot similar trends, and research who else has thunk such thoughts before you. In short, you need to do your homework and critically think about it over time.

In performance-blog-land you do that thinking and researching privately, then shove it out at the final moment. A grand flourish that hides the process.

In garden-land, that process of researching and refining happens on the open internet. You post ideas while they’re still “seedlings,” and tend them regularly until they’re fully grown, respectable opinions.

This has a number of benefits:

- You’re freed from the pressure to get everything right immediately. You can test ideas, get feedback, and revise your opinions like a good internet citizen.

- It’s low friction. Gardening your thoughts becomes a daily ritual that only takes a small amount of effort. Over time, big things grow.

- It gives readers an insight into your writing and thinking process. They come to realise you are not a magical idea machine banging out perfectly formed thoughts, but instead an equally mediocre human doing The Work of trying to understand the world and make sense of it alongside you.

This all comes with an important caveat; gardens make their imperfection known to readers. Which brings us to the next pattern…

3. Imperfection & Learning in Public

Gardens are imperfect by design. They don’t hide their rough edges or claim to be a permanent source of truth.

Putting anything imperfect and half-written on an “official website” may feel strange.

We have all been trained to behave like tiny, performative corporations when it comes to presenting ourselves in digital space. Blogging evolved in the Premium Mediocre culture of Millenialism as a way to Promote Your Personal Brand™ and market your SEO-optimized Content.

Weird, quirky personal blogs of the early 2000’s turned into cleanly crafted brands with publishing strategies and media campaigns. Everyone now has a modern minimalist logo and an LLC.

Digital gardening is the Domestic Cozy response to the professional personal blog; it’s both intimate and public, weird and welcoming. It’s less performative than a blog, but more intentional and thoughtful than a Twitter feed. It wants to build personal knowledge over time, rather than engage in banter and quippy conversations.

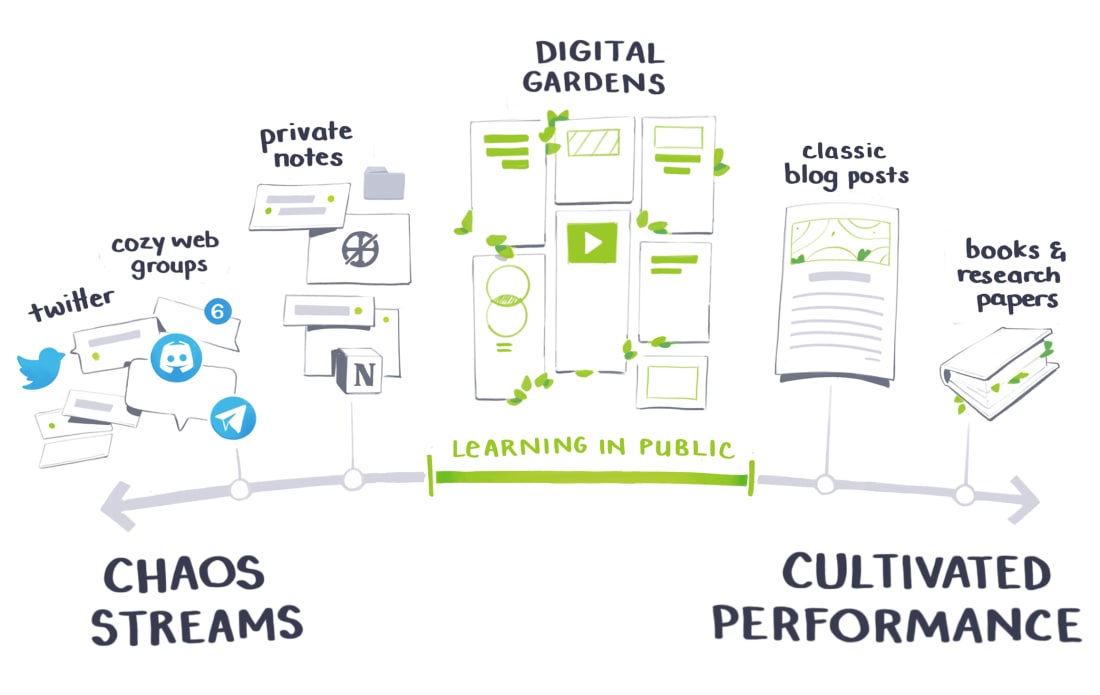

Think of it as a spectrum. Things we dump into private WhatsApp group chats, DMs, and cavalier Tweet threads are part of our chaos streams - a continuous flow of high noise / low signal ideas. On the other end we have highly performative and cultivated artefacts like published books that you prune and tend for years.

Gardening sits in the middle. It’s the perfect balance of chaos and cultivation.

This ethos of imperfection opens up a world of possibility that performative blogging shut down. First, it enables you to Learn in Public; the practice of sharing what you learn as you’re learning it, not a decade later once you’re an “expert.”

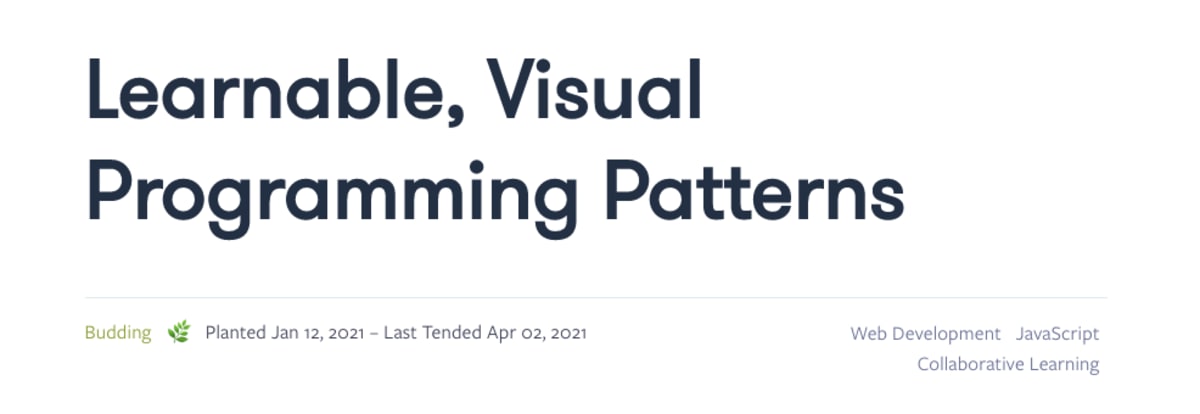

This freedom of course comes with great responsibility. Publishing imperfect and early ideas requires that we make the status of our notes clear to readers. You should include some indicator of how “done” they are, and how much effort you’ve invested in them.

This could be with a simple categorization system. I personally use an overly horticultural metaphor:

- 🌱 Seedlings for very rough and early ideas

- 🌿 Budding for work I’ve cleaned up and clarified

- 🌳 Evergreen for work that is reasonably complete (though I still tend these over time).

I also include the dates I planted and last tended a post so people get a sense of how long I’ve been growing it.

Other gardeners include an epistemic status on their posts – a short statement that makes clear how they know what they know, and how much time they’ve invested in researching it.

was one of the earliest and most consistent gardeners to offer meta-reflections on their work. Each entry comes with:

- topic tags

- start and end date

- a stage tag: draft, in progress, or finished

- a certainty tag: impossible, unlikely, certain, etc.

- 1-10 importance tag

These are all explained in their

, which is worth reading if you’re designing your own epistemological system.

The metadata available on each of Gwern’s essays

Devon Zuegal is another notable gardener who has epistemic status and epistemic effort on their posts, indicating both their certainty level about the material, and how much effort went into making it. They also make a strong case for

as a feature, not a bug.

Epistemic effort and epistemic status metadata at the top of Devon Zuegal’s writing

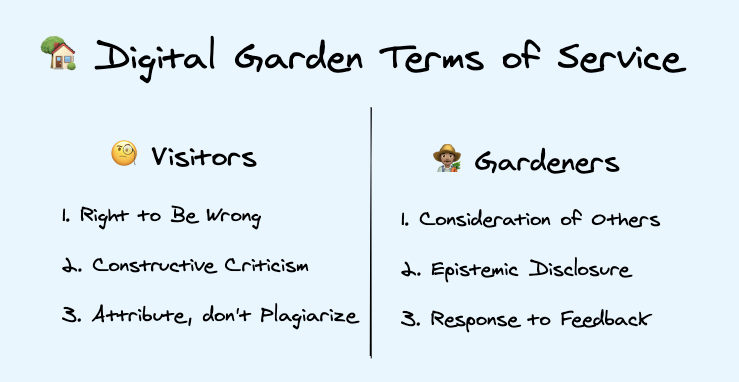

In a similar vein, Shawn Wang has written the Digital Gardening

which I adore and ascribe to. They ask the reader to allow the writer to be wrong, offer constructive criticism, and attribute their work. They ask gardeners to be considerate of others (don’t share private information or name and shame), offer epistemic disclosure, and respond to feedback.

All of these design patterns feed our growing desire for transparency, meta information, and breadcrumbs back to the source of ideas.

4. Playful, Personal, and Experimental

Gardens are non-homogenous by nature. You can plant the same seeds as your neighbour, but you’ll always end up with a different arrangement of plants.

Digital gardens should be just as unique and particular as their vegetative counterparts. The point of a garden is that it’s a personal playspace. You organise the garden around the ideas and mediums that match your way of thinking, rather than off someone else’s standardised template.

Ideally, this involves experimenting with the native languages of the web – HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. They’re the most flexible and robust tools we have for building interconnected knowledge online. Gardens are a chance to question the established norms of a ‘personal website’, and make space for weirder, wilder experiments.

That said, I should acknowledge that jumping into full-on web development is simply beyond the abilities and interests of many people. There is still room for personalisation and play if you’re using a pre-made template or service – it’ll just be within the constraints of that system.

One goal of these hyper-personalised gardens is deep contextualisation. The overwhelming lesson of the Web 2.0 social media age is that dumping millions of people together into decontextualised social spaces is a shit show. Devoid of any established social norms and abstracted from our specific cultural identities, we end up in awkward, aggravating exchanges with people who are socially incoherent to us. We know nothing of their lives, backgrounds, or belief systems, and have to assume the worst. Twitter only offers us a 240 character bio. Facebook pre-selects the categories it deems important about you – relationship status, gender, hometown.

Gardens offer us the ability to present ourselves in forms that aren’t cookie cutter profiles. They’re the higher-fidelity version, complete with quirks, contradictions, and complexity.

5. Intercropping & Content Diversity

Gardens are not just a collection of interlinked words. While linear writing is an incredible medium that has served us well for a little over 5000 years, it is daft to pretend working in a single medium is a sufficient way to explore complex ideas.

It is also absurd to ignore the fact we’re living in an audio-visual cornucopia that the web makes possible. Podcasts, videos, diagrams, illustrations, interactive web animations, academic papers, tweets, rough sketches, and code snippets should all live and grow in the garden.

Historically, monocropping has been the quickest route to starvation, pests, and famine. Don’t be a lumper potato farmer while everyone else is sustainably intercropping.

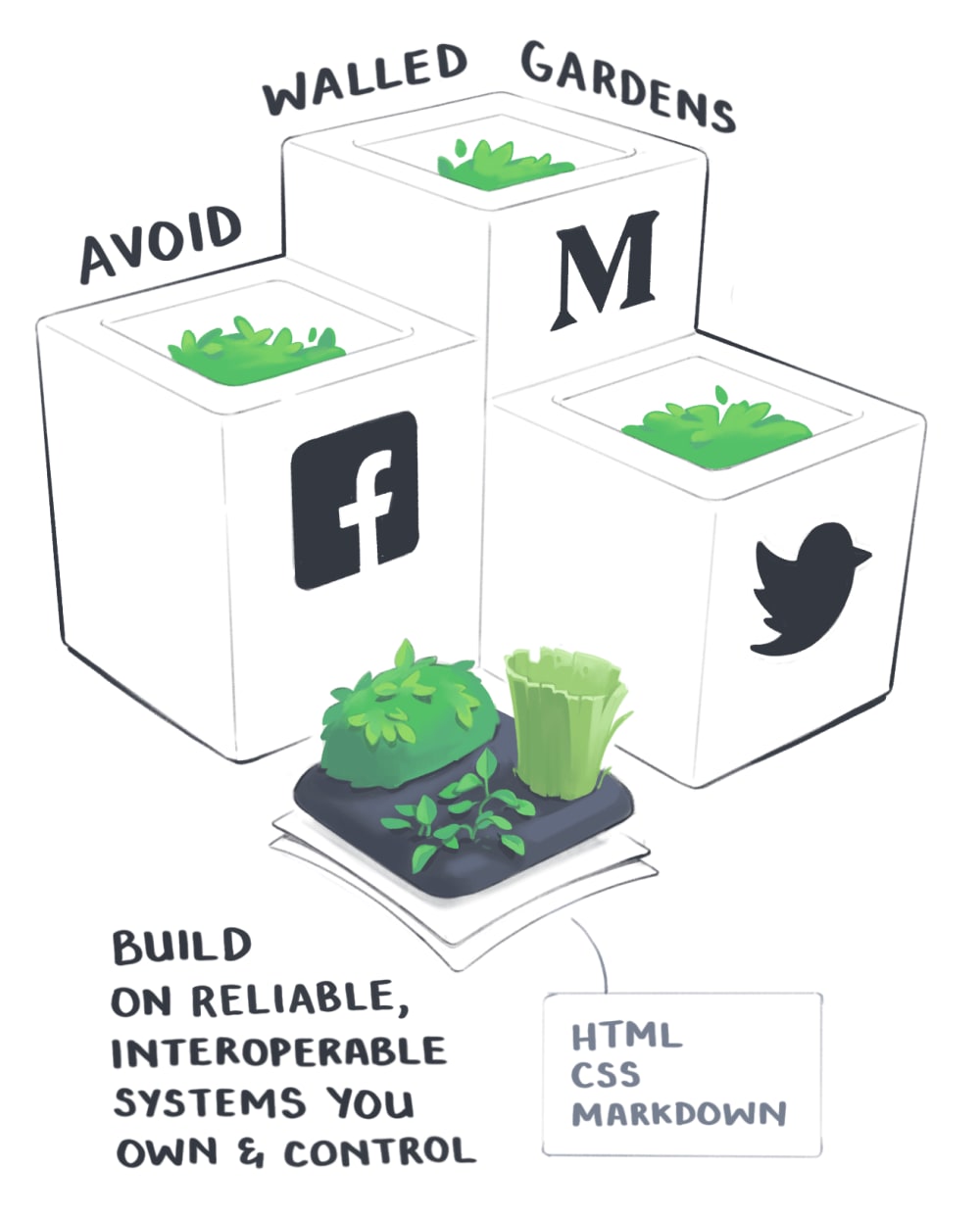

6. Independent Ownership

Gardening is about claiming a small patch of the web for yourself, one you fully own and control.

This patch should not live on the servers of Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, Instagram (aka. also Facebook), or Medium. None of these platforms are designed to help you slowly build and weave personal knowledge. Most of them actively fight against it.

If any of those services go under, your writing and creations sink with it (crazier things have happened in the span of humanity). None of them have an easy export button. And they certainly won’t hand you your data in a transferable format.

Independently owning your garden helps you plan for long-term change. You should think about how you want your space to grow over the next few decades, not just the next few months.

If you give it a bit of forethought, you can build your garden in a way that makes it easy to transfer and adapt. Platforms and technologies will inevitably change. Using old-school, reliable, and widely used web native formats like HTML/CSS is a safe bet. Backing up your notes as flat markdown files won’t hurt either.

Keeping your garden on the open web also sets you up to take part in the future of gardening. At the moment our gardens are rather solo affairs. We haven’t figure out how to make them multi-player. But there’s an enthusiastic community of developers and designers trying to fix that. It’s hard to say what kind of libraries, frameworks, and design patterns might emerge out of that effort, but it certainly isn’t going to happen behind a Medium paywall.